Page Content

The Working Lives of Teachers

What does research tell us?

For every teacher who leaves the school, there are many who stay. What … keeps them believing and demonstrating daily that they can and do continue to ‘make a difference’ in the lives of the children they teach is, therefore, hugely important. … Burnout and attrition, about which there is so much concern, may be the tip of an enormous iceberg. What lies beneath the surface? What factors help or hinder the capacity of those who are more experienced to teach to their best? Who are these so-called veterans?

—Christopher Day and Qing Gu, The New Lives of Teachers

Few passages from the vast body of research on teachers’ work speak more eloquently than this one, which is by the authors of the groundbreaking book The New Lives of Teachers by Christopher Day and Qing Gu. The New Lives of Teachers offers important insights into the interrelationship between teachers’ personal everyday lives and identities and how they factor into schools and educational organizations.

Much Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA) research reinforces many of Day and Gu’s conclusions, particularly those related to how teachers’ conditions of practice are one of the most important but least understood indicators of organizational effectiveness. This is ironic, given the government’s focus on measurement and accountability.

What does the research tell us about the current conditions of practice in Alberta’s schools? What are the trends and drivers shaping the tone and texture of teachers’ everyday working lives? What might influence the quality of Alberta schools in the future, given that teachers’ conditions of practice are students’ learning environments?

What is clear in recent ATA research and Day and Gu’s work is that the narrow focus on indicators of difficulty—attrition, teacher stress or deteriorating classroom conditions—fails to illuminate the complex relationship of the forces that support and/or diminish teachers’ work lives.

We know that most Alberta teachers have long and rewarding careers and report high degrees of satisfaction with teaching. But what we don’t know or understand is the relationship between the complex variables that shape teachers’ work over time. Day and Gu describe how social, economic and political forces affect teachers' lives, and emphasize that these forces can be understood only by examining the intersection of teachers’ personal experiences with the formal institutional structures and processes in schools.

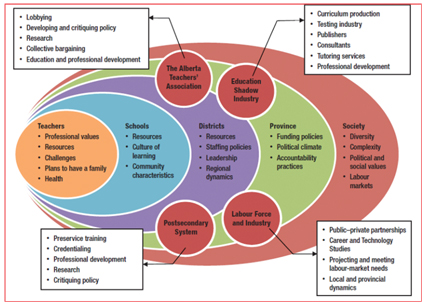

The accompanying diagram, The Work Life of Teachers: A System Model, shows the interplay of institutional, economic and psychosocial factors that influence teachers’ work in Alberta. This model, which was initially developed as part of the ATA’s five-year study of a cohort of 135 beginning teachers in 2008,[1] has a clear message—the factors that shape teachers’ work can’t be easily isolated, and this poses difficulties for those advocating for improving conditions of practice.

The Work Life of Teachers: A System Model

Diagram 1: The Work Life of Teachers: A System Model

If you start with teachers (far left bubble) and move through to schools, districts, province and society, you get a picture of the broader societal forces influencing teachers’ work. Within each of these domains, examples of direct and indirect influences on teachers’ work are identified (for example, resources and funding).

The effect of any one of these factors on schools and teaching varies considerably. For example, the influence of the labour force and industry on schools is evident through the growth of private–public partnerships in the education sector. In September 2010, six public and three Catholic schools opened in Edmonton using the P3 model. Yet, community agencies such as the Edmonton Federation of Community Leagues and the YMCA now complain that the P3 contracts prohibited school boards from leasing space in the schools to outside groups (Sands 2012). Rather than seeing schools as hubs of their communities, current P3 models see schools merely as buildings in which to house students during the school day.

Another factor influencing teachers’ work life is the test-based accountability system that has contributed to the growth of private-for-profit test-preparation services. One-third of parents in Alberta report having hired private tutors for their children, even though their children were on the honour roll.[2] The overheated culture of test performance in many Alberta school jurisdictions diminishes the work of teachers and student learning.[3] Increasingly, Alberta companies are aggressively marketing student reporting software. The resulting negative effect on teachers’ work lives is well documented. In Alberta, there are more than 15 different digital reporting platforms of varying levels of usefulness and efficiency in use. In a study of the impact of digital reporting tools in Alberta schools (AAC and ATA 2011), more than 50 per cent of respondents stated that their workload had increased an average of 15 hours per term. Many respondents (78.2 per cent) indicated that they didn’t have any input into the choice and implementation of the reporting tool.

Other influences on teachers’ work: Attrition, induction and retention

Though research on teacher attrition, induction and retention has been conducted from a variety of perspectives, there is a growing consensus that supports and barriers to teachers’ professional growth are encountered in relationships and institutions where teachers forge their craft knowledge, expertise and identities.[4] In fact, given the growing variance in teacher satisfaction, efficacy and conditions of practice, ATA research continues to ask the rhetorical question: Is there really an education system in Alberta or do we have a bunch of loosely connected schools that are inscribed by the arbitrary boundaries of school jurisdictions?

On this note, one factor that merits closer attention is the effect of school culture on teachers’ work (one third-year teacher who is part of the cohort of 135 teachers followed since 2008 said of an attempt to develop a school improvement project: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” In early career learning and identity formation, teachers take their cues from many formal and informal elements of their immediate environments, including mentors, colleagues, administrators, students and parents (Melnick and Meister 2008). And, as the ATA’s five-year study of beginning teachers shows (ATA 2011a), these elements form a rich, if not always problem-free, interpersonal dimension when a school’s culture places excessive focus on extracurricular activities or taking on larger classes to help the school budget out.

The topic of teacher attrition has emerged in a number of ATA studies, notably in The Early Years of Practice—Interim Report of a Five-Year Study of Beginning Teachers (ATA 2011a). As the study outlines, some research relies on objective measures of demographic variables (Alberta Education 2010), whereas other research focuses on the subjective experiences of new teachers (Goddard and Foster 2001; Hong 2010). Still other research, focusing on resilience, self-confidence and efficacy, is used to assess the psychological tools and skills that teachers bring to their work. Social background, past school experiences, preservice training, race, class and gender are among the variables that shape individual personalities (Achinstein, Ogawa and Speiglman 2004).

Extending into the sociocultural milieu of the school, some research considers how individual teachers learn about and negotiate these micropolitics and interprofessional relationships (Day and Gu 2010; Kardos and Johnson 2007). Clark and Antonelli (2009) examine teacher attrition in Ontario and take into consideration the elimination of mandatory retirement, projected teacher retirements, graduation rates from teacher preparation programs and declining school enrolments. Still other studies have compared teachers’ working conditions and attrition rates to those of other professions, lending perspectives from beyond the public education sector (Guarino, Santibanez and Daley 2006; Johnson et al. 2005).

Too often we see teachers’ work in Alberta schools shaped by what Andy Hargreaves (2009) described as “the perniciousness of the present,” where what is considered common sense has little, if any, basis in research and sound practice. Though learning communities and collaboration focused on enhancing student learning are laudable, it is naive to ignore the collateral effects on teachers’ sense of self-efficacy in a school with a singular focus on data-driven decision making or best practice. Community and collaboration are never neutral in their effects on teacher identity and professional autonomy. Collegial relationships, while important, can obscure the structural and systemic conditions that are beyond the control of individual teachers and, often, individual schools (Grossman and Thompson 2004). These conditions might include competition in times of budget constraints, the unsustainability of Alberta’s excessively long school days and school operating calendars,[5] ambiguous hiring and promotion practices, and the characteristics of communities challenged by high transiency and poverty. Perhaps the “perniciousness of the present” explains why new and experienced teachers alike have come to accept that the average teacher in Alberta works an average of 56 hours a week.[6]

Given the high quality of Alberta’s teaching force, it’s important that research be pursued to assure that the future of teachers’ work will be a rich and vibrant professional experience. High-quality teaching means enhanced learning for all students. A vigorous commitment to research and evidence-informed policy to sustain and support quality teaching must be a priority for the K–12 education sector.

References

Achinstein, B., R. T. Ogawa and A. Speiglman. 2004. “Are We Creating Separate and Unequal Tracks of Teachers? The Effects of State Policy, Local Conditions, and Teacher Characteristics on New Teacher Socialization.” American Educational Research Journal 41, no. 3: 557–603.

Anagnostopoulos, D., E. R. Smith and K. G. Basmadjian. 2007. “Bridging the University–School Divide: Horizontal Expertise and the ‘Two-Worlds Pitfall.’” Journal of Teacher Education 58, no. 2: 138–152.

Alberta Assessment Consortium (AAC) and the Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA). 2011. The Impact of Digital Reporting Tools in Alberta Schools: A Collaborative Research Study (2008–2011). Edmonton, Alta.: Alberta Assessment Consortium and the Alberta Teachers’ Association.

Alberta Education. 2010. Education Sector. Workforce Planning. Framework for Action. Available at http://education.alberta.ca/media/1155749/2010-03-03 education sector workforce planning framework for action.pdf. (accessed May 1, 2012).

Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA). 2011a. The Early Years of Practice—Interim Report of a Five-Year Study of Beginning Teachers. Edmonton, Alta.: ATA.

———. 2011b. The New Work of Teaching—A Case Study of the Work Life of Calgary Public Teachers. Edmonton, Alta.: ATA.

Clark, B. R., and F. Antonelli. 2009. Why Teachers Leave: Results of an Ontario Survey 2006–08. Ontario Teachers’ Federation and Government of Ontario. Available at www.otffeo.on.ca/english/media_briefs.php. (accessed November 3, 2010).

Day, C., and Q. Gu. 2010. The New Lives of Teachers. London and New York: Routledge.

Gariepy, K. D., B. L. Spencer and J. C. Couture (eds.). 2009. Educational Accountability—Professional Voices from the Field. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

Goddard, J. T., and R.Y. Foster. 2001. “The Experiences of Neophyte Teachers: A Critical Constructivist Assessment.” Teaching and Teacher Education 17: 349–65.

Grossman, P., and C. Thompson. 2004. “District Policy and Beginning Teachers: A Lens on Teacher Learning.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 26, no. 4: 281–301.

Guarino, C. M., L. Santibanez and G. Daley. 2006. “Teacher Recruitment and Retention: A Review of the Recent Empirical Literature.” Review of Educational Research 76, no. 2: 173–208.

Hargreaves, A. 2009. “Real Learning First through the Fourth Way: An Invitational Symposium.” Public lecture given in Calgary, Alta., April 28.

Hong, J. Y. 2010. “Pre-Service and Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity and its Relation to Dropping Out of the Profession.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26, no. 8: 1530–43.

Johnson, S., C. Cooper, S. Cartwright, I. Donald, P. Taylor and C. Millet. 2005. “The Experience of Work-Related Stress across Occupations.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 20, no. 2: 178–187

Kardos, S. M., and S. M. Johnson. 2007. “On Their Own and Presumed Expert: New Teachers’ Experience with Their Colleagues.” Teachers College Record 109, no. 9: 2083–2106.

Sands, A. 2012. “P3 School Model Needs Restructuring: Educators, Government, Parents Want Restrictions Loosened.” Edmonton Journal, March 26.

Melnick, S., and D. G. Meister. 2008. “A Comparison of Beginning and Experienced Teachers’ Concerns.” Educational Research Quarterly 31, no. 3: 39–56.

____________________________

Dr. J-C Couture is the ATA’s associate coordinator, research.

[1] Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA). 2011. The Early Years of Practice—Interim Report of a Five-Year Study of Beginning Teachers. Edmonton, Alta: ATA. This study, led by Laura Servage, forms the basis of many of the observations made in this article.

[2] See Changing Landscapes for Learning Our Way to the Next Alberta. 2010. Alberta Teachers’ Association and Cambridge Strategies.

[3] For a detailed analysis of the influences on teaching and learning processes within the current accountability regime in Alberta, see Kenneth D. Gariepy, Brenda L. Spencer and J. C. Couture (eds.). 2009. Educational Accountability—Professional Voices from the Field.

[4] Achinstein, B., R.T. Ogawa and A. Speiglman (2004, p. 558) describe a “multilayered system” of “district and school characteristics, state educational policies, and teachers’ backgrounds” that “interact to shape the socialization of new teachers.”

[5] We need to learn from the successes of high-performing jurisdictions, such as Finland, where teachers teach just under 600 hours per school year, while Alberta teachers typically teach more than 1,000 hours. A study of Calgary public teachers (May 2011) found that respondents’ average work week of 55 hours included 22 hours on the core tasks of instruction and planning. Additional instructional work (assessment and reporting/communication) takes up almost six hours a week during working hours.

[6] See The New Work of Teaching—A Case Study of the Work Life of Calgary Public Teachers. 2011. Edmonton, Alta.: ATA.